Establishing a rapport with a serial killer is not for the faint of heart.

It was far and away the most daunting hurdle for me in researching my book, Kitty Genovese: A True Account of a Public Murder and its Private Consequences. The killer in question, Winston Moseley, who died in prison on March 28, 2016 at the age of 81, was never well known by name but his crime—or more accurately, one of his crimes—captured worldwide attention more than 50 years ago and has steadily lurked in the darker recesses of the public consciousness ever since.

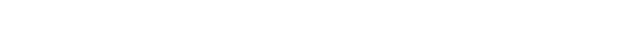

The grisly 1964 murder of Kitty Genovese in Kew Gardens, Queens remains to this day one of the most studied and cited homicide cases in American history, mainly due to inflammatory reports that multiple witnesses in the nice middle-class neighborhood where it happened failed to heed Genovese’s screams and pleas for help. The case has been exhaustively picked apart to unearth the mystery of bystander inaction. But what about the man who actually committed the murder?

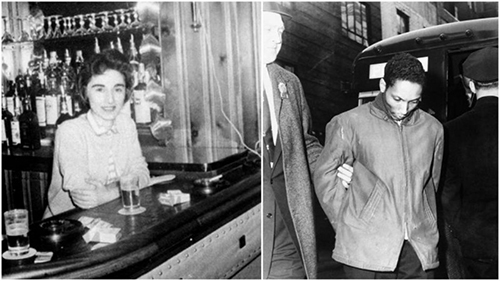

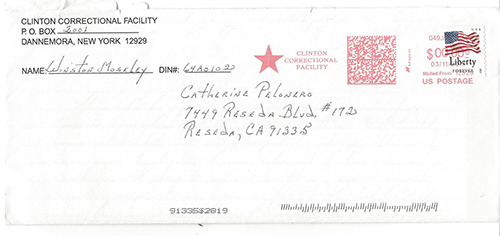

Winston Moseley was 74 years old when I began my years-long correspondence with him. He had been incarcerated in various New York prisons since he was 29 years old, when his conviction for Kitty’s murder landed him first on death row in Sing Sing and then permanent residency in the correctional system after his sentence was commuted to life with the possibility of parole.

There was very little information available about Winston Moseley when I started writing to him. Ironically, his role in the murder of Kitty Genovese had been almost completely overlooked by both media and academia, overshadowed by the intense interest in the witnesses. But a closer look at Winston Moseley may shed light on the workings of a dangerous mind.

My major focus in writing the book was to give a full portrait of Kitty Genovese—who she was, who she had hoped to become when her life was stolen at the age of 28. In order to tell the most complete account of the story possible, however, I felt it was essential to also give an accurate portrayal of her killer. In my very first letter I let Moseley know my objective; I was writing a book about Kitty Genovese and to that end I wanted to interview him, his family, his friends. He wrote back to express his disgust. He hadn’t given an interview in decades and had no interest in doing so now. Unlike some high-profile killers, Moseley eschewed the limelight. He didn’t want publicity, had no desire to speak about his crimes or offer himself as an “expert,” a la Ted Bundy, on predators like himself. What he wanted most of all was to get out of prison, and that wasn’t likely to happen as long as people remembered what he had done to Kitty.

I wrote back and told him, quite honestly, that I wasn’t interested in discussing his crimes. Frankly it didn’t seem necessary since he had long ago given very detailed confessions. I already knew what he had done; I needed to know who he was. Talking about himself apart from his criminal notoriety suited Moseley. Like all sociopaths and many serial killers, he was a narcissist at heart.

Over time he gave me a detailed account of his childhood and pre-prison life. He sent me poems and letters he had written, photos of his family, interview requests he received from journalists and filmmakers (all of which he turned down), letters he got from the occasional academic or student and more often from curiosity seekers, along with a collection of romantic and/or pornographic messages sent to him by women he had never met, including at least one marriage proposal.

A chapter in my book gives an account of Winston’s Moseley background from his gloomy childhood through his descent into robbery, rape, and murder. I’ve taken some criticism from people who feel that writing about Moseley as anything other than a “monster” somehow constitutes a lack of empathy for his victims. I disagree. On the contrary, I think the more that can be learned about the lives and psyches of serial killers, the better prepared we might be to stop them and possibly thwart others with similar proclivities before they venture down that path.

Few people know that Winston Moseley gave several different versions over the years of what “really” happened the night Kitty Genovese died. The first account he gave to the NYPD back in 1964, his confession, matched physical evidence from the crime. It was also far and away the most credible, because it was true. After a few years in prison, however, and deciding that he’d rather be free again, Moseley got creative in his recollections. I recently spoke with a woman who exchanged letters with him in the early 1970s. The woman was a college student at the time and a course she was taking required students to correspond with assigned inmates at Attica Correctional Facility. Moseley wrote her that Kitty’s murder had been a crime of passion; he claimed that he and Kitty had been having an illicit affair and that he killed her out of jealousy, and of course he deeply regretted his momentary loss of control. By all accounts and every shred of evidence, this is a complete fabrication. In his letters to this college student, Moseley admitted he had been a burglar but didn’t reveal his other rapes or murders. Before the Internet made information and old news readily available, Moseley apparently thought he could suppress, twist, and rewrite as he saw fit, and who would be the wiser?

In 1979, in the last interview he granted to a media outlet, Moseley explained to the producers of the show 20/20 that it all started with road rage. He alleged that Kitty had cut him off in traffic and hurled a racial epithet at him before speeding off. He followed her home that night because he simply wanted to confront her about the nasty word she had called him, but one thing led to another. Asked to comment on this new scenario, Moseley’s own lawyer, Sidney Sparrow, called it “absurd.”

When he finally decided to tell me about it, the first version he gave was that he hadn’t killed Kitty Genovese at all. Some other man had done it, but Moseley had unwittingly been conned into driving the getaway car. In my reply I bluntly told him it didn’t ring true and I’d prefer he just say nothing about it rather than write lies. When he wrote back he sort of complimented me on dismissing his getaway car explanation. It was some time later that he gave me another edition of the murder, this time admitting that he had in fact killed Kitty Genovese but not because he wanted to. He had fallen in with the wrong crowd and gangsters had forced him to do it as a contract killing.

He knew I didn’t buy it. That didn’t stop him from trying to sell it, although that was the last time he tried to feed me a wild bunch of oats on the murder. Over time he wrote a bit more truthfully about his crimes, although mainly to point out that they had all happened a long time ago. One of the last mentions he ever made about Kitty Genovese came in one of the last letters I ever received from him, in which he said that he wanted to apologize to me for “his part in her death.”

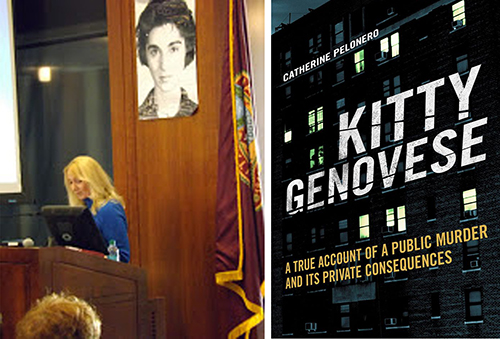

Catherine Genovese Memorial Conference at Fordham University, March 2014

Amid the fabrications and attempts at manipulation, when he was off his guard Moseley did reveal things about himself that he undoubtedly viewed as trivial but which I found very telling. Recounting his childhood, he once offhandedly wrote that he had been rendered unconscious after being hit in the head by a streetcar. He wrote about his parents’ separation and his mother suddenly leaving him behind, after which he was sent to live with various relatives in Michigan. From the age of nine until his late teens, Winston only saw his mother a couple of times a year, whenever she decided to drop in for a few days to say hello. He claimed to harbor no resentment against his mother and I believe he didn’t, at least not consciously.

I once asked him who he felt had actually raised him, considering how he had been shuffled around so much as a child, and he replied that his parents had raised him. When I carefully suggested that maybe his mother had not given him as much maternal care and consideration as she might have—which is quite the understatement, but I learned early on that he frowned on any criticism of his mother—he firmly defended her, writing that he knew throughout his boyhood that if he had ever really needed her, she would have come right away.

In addition to her neglect and abandonment of her only child, Fannie Moseley was chronically, flagrantly unfaithful to her husband, Al Moseley, who nevertheless maintained a slavish devotion to her. After his first round of pleas to reconcile with Fannie were unsuccessful—she agreed to remain married to him but insisted on keeping her lover too—Al Moseley eventually moved to Michigan and assumed care of Winston. Fannie Moseley never seemed to “get” the need for considering anyone’s feelings but her own. There’s a good case to be made that Fannie was a sociopath herself.

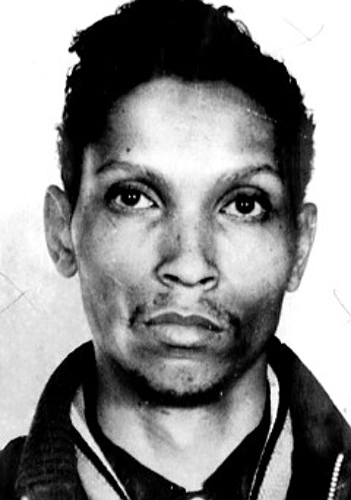

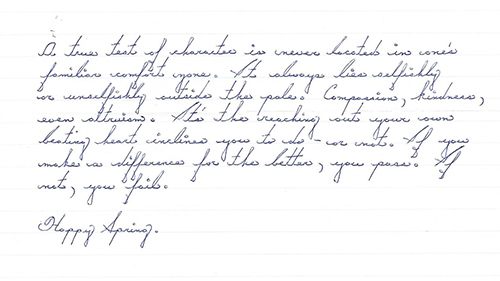

Snippet from one of Moseley’s handwritten letters to me, explaining his thoughts on what makes a “true test of character.”

Winston’s first wife shared some striking similarities with his mom. She was also a philanderer who made little effort to hide her affairs or pay any mind to the humiliation she caused her husband. In letters to me, Moseley defended her as well, explaining that she just hadn’t been ready for marriage.

Moseley learned in his late teens that Al Moseley, the man he had called “daddy” his whole life, was not his biological father. Al sprang this news on him during an argument that started when Winston told Al that he intended to move away from Michigan in order to live closer to Fannie. Winston at first refused to believe it was true. Never one to confront his mother about anything, he didn’t hear it from her until years later at his murder trial, when Fannie said it in open court.

Moseley’s mother never told him the identity of his biological father but she did tell his first wife, who, many years after Moseley had been sent to prison, eventually relayed the information to him. Fannie told her daughter-in-law that Winston’s biological father was a Jewish man, a former employer of Fannie’s who had raped her. Divulging this information in a letter to me, Moseley speculated that if it was true, which he seemed to believe it was, it might explain why he had always gotten along so well with Jewish people.

As intelligent and cunning a man as Moseley was, he genuinely seemed to have no insight at all when it came to himself or what motivated him to veer into a double life as a responsible family man by day and merciless killer by night. At the time he began his criminal exploits he was in his late 20s, remarried to a faithful and devoted second wife. He had a good career and earned a comfortable living, owned his home, and dutifully paid child support to his former wife. As for why he did the evil things that he did, he seemed to be as much at a loss for an explanation as everybody else. All he knew was that somehow he developed an uncontrollable urge to harm and kill women.

It’s impossible to say with certainty why a person chooses to inflict pain and death on strangers who have done him no harm. But a closer look at an offender’s personal history yields some undeniable clues. Could it be just coincidence that Moseley prowled for victims in neighborhoods where his mother had either worked or once lived?

Of course, he wasn’t hunting for his mother per se. He knew exactly where to find her, since Fannie had come to live in the house Winston shared with his second wife and their baby. Ever the dutiful son, he never complained or expressed any bitterness when the mother who had abandoned him took up residence in his home. He even built an apartment for her within the house, to give her comfort and privacy. Winston quietly tolerated his mother’s conduct, the way she bounced back and forth between his house, her lover’s apartment, and the home of her husband, Al Moseley, with whose affections she still toyed. Shortly after his mother moved in, Moseley began his clandestine attacks on women.

In the irony of ironies, Fannie Moseley loudly decried what she viewed as the public’s gross insensitivity to her son after his conviction. She bemoaned the unfairness of his long prison sentence, pointing to all the promise he had shown as a young man. Winston could have been a productive member of society, Fannie felt, if people would have treated him decently.