He heard orders to kill, and, as a soldier, he always followed orders. During a late-1980 killing rampage from one end of New York State to the other, he killed at least 10 black and Hispanic males, and wounded four others.

The attacks started and ended in Western New York, creating a climate of terror for African-Americans across the region.

Joseph G. Christopher was implicated in four fatal shootings and six deadly stabbings in Western New York and New York City from late September 1980 through the end of the year. Three attacks occurred in Buffalo, and one each in Cheektowaga, Niagara Falls and Rochester.

Before the killings were connected and Christopher identified, the press gave him two nicknames: the .22-Caliber Killer in Buffalo and the Midtown Slasher in Manhattan.

After his capture and confinement in jail and psychiatric centers, Christopher was sentenced to at least 58½ years in prison before dying of cancer there in 1993. He was 37.

Now, more than 35 years later, Christopher’s tragic case has come to life again, as author Catherine Pelonero, who grew up in Buffalo, is writing a book about his rampage. Her last non-fiction book, “Kitty Genovese: A True Account of a Public Murder and Its Private Consequences,” was published in 2014 and rose to No. 11 on the New York Times Best Seller list.

No one will ever know for sure how many people Joseph Christopher killed. Buffalo homicide detectives debated for decades whether Christopher also killed two black taxi drivers whose hearts were removed from their bodies in October 1980.

In a 1983 interview with a Buffalo News reporter inside New York City’s Rikers Island prison, Christopher admitted to being a serial killer.

“I could kill somebody,” he said. “I have.”

“How many people?” he was asked.

“I believe 13.”

Pelonero, in an interview in her brother’s East Amherst home, implied that the killings might have been prevented.

Christopher, who suffered from paranoid schizophrenia, had reached out for help after noticing his mental health deteriorating in 1978, she said. He even tried to admit himself to the Buffalo Psychiatric Center in September 1980.

Center officials told him he wasn’t a danger to himself or others, Pelonero discovered, a common standard at a time when such centers were being downsized. Instead, the officials recommended counseling.

Fourteen days after he walked away from the center, the killings began.

Change of weapons

The first four victims were shot to death over 36 hours, starting at about 10 p.m. Sept. 22, 1980.

First was Glenn Dunn, 14, shot twice while sitting in an idling car in front of a Genesee Street supermarket. Then Harold Green, 32, struck twice while eating in a Cheektowaga Burger King parking lot. Then Emmanuel Thomas, 30, hit once while crossing the street near his Buffalo home. And finally, Joseph L. McCoy, 43, shot twice in Niagara Falls.

The similarities were striking. Some witnesses saw a young white male shooter. All four victims were shot in the left side of the head.

And all were black males.

Ballistics tests soon showed that all had been killed with the same .22-caliber gun.

Three months later, a serial killer was at work in New York City. This killer used a knife while attacking six people, five black and one Hispanic, on Manhattan streets within a 13-hour period on Dec. 22, 1980, authorities said. Four of those six died.

A week later, a serial slasher struck Western New York, killing Roger Adams, 31, of Buffalo, and a Rochester man before wounding two Buffalo men, all between Dec. 29 and Jan. 1.

A few days later, authorities announced that the wave of stabbings was “probably linked” to Buffalo’s unsolved .22-caliber shootings.

The case broke open in the spring.

Christopher extradited from Georgia

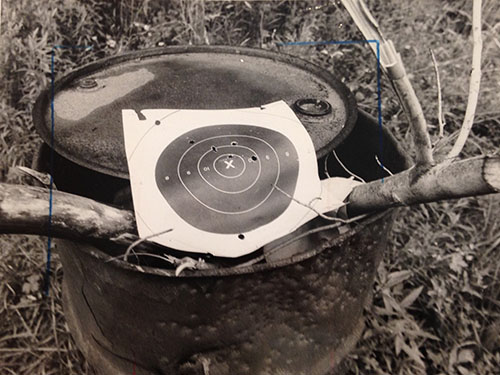

Army Pvt. Joseph G. Christopher – who had been arrested at Fort Benning, Ga., and accused of slashing a black soldier – was hospitalized with self-inflicted wounds. Christopher told two Army psychiatric nurses about the killings of black men in Buffalo. He was indicted in April 1981 on the first three Buffalo killings, and brought back here May 8.

The motive

Pelonero believes she knows Christopher’s motive.

“It was fear,” she said. “It was a paranoid schizophrenic killing out of fear. Actually, that’s an understatement. It was abject terror. Paranoid schizophrenics totally believe their own delusions, that they have something to fear, that they are under attack.”

Others realize those are delusions, Pelonero said. But to paranoid schizophrenics, those dominating feelings become reality.

“I would compare paranoid schizophrenia to living in a nightmare from which you can’t wake up,” she said.

How about the racial angle in the attacks?

“It could have been black men,” she said of the victims. “It could have been redheads. It could have been people with blue eyes. It could have been short people.”

But it wasn’t those other groups. It was black people and one dark-skinned Hispanic man.

Many law enforcement officials agreed with the late Buffalo Homicide Chief Leo J. Donovan that Christopher’s rage stemmed from blaming blacks for his late father’s handgun collection being taken from him. His pistol permit had been revoked for target shooting at a local college pistol range.

Pelonero pointed instead to the pattern of racial tension and prejudice Christopher experienced growing up on Weber Avenue in the city’s Bailey-East Delavan area and at Burgard Vocational High School.

“The neighborhood was changing, and there was a lot of tension,” she said.

Through interviews with Christopher’s former neighbors, teachers and boyhood friends, Pelonero found incidents from his youth that could have influenced his outlook on black people, especially when his mind deteriorated under paranoid schizophrenia.

Joseph Christopher in a high school yearbook photo

Two examples from his neighborhood and school: Groups of white and black kids yelling at each other on the streets. And the early-1970s racial bullying at Burgard, where, Pelonero was told, blacks would surround a white kid going to school, demanding a dollar to ensure his safety.

“It seems possible that that’s how the fears arose, from the racism he had experienced growing up,” she said.

Frightened community

It’s hard for outsiders to fathom the fear that gripped Buffalo’s black community in the fall of 1980 following the news that the same white man committed the first four shootings.

Black people started carrying weapons for protection. In early October, police found the remains of the two cab drivers. The community seemed on the verge of race riots.

“Buffalo suddenly gained unwanted national attention, and after Karl Hand, a racist white supremacist, announced plans for a rally, a crowd of 5,000 people gathered on the steps of City Hall for a ‘Unity Day Rally,’ decrying racism and the killings,” The Buffalo News recounted in 1993, after Christopher died.

Buffalo’s black community was scared – but mobilized.

Still, the attacks continued. The .22-Caliber Task Force developed more than 2,000 possible suspects, but many African-Americans questioned whether authorities were doing enough to find the killer.

Target photographed at Christopher’s hunting cabin

“The fear in the black community was just overwhelming,” retired Appellate Division Justice Samuel L. Green recalled last week. “You were scared to death, because you didn’t know who this person was going to hit next.”

Green, who is black, started carrying his handgun during that time, and he believes Christopher may have brushed up against him on Court Street one day.

On a curious note, the judge wound up arraigning Christopher in State Supreme Court.

How many did he kill?

Court rulings first found Christopher incompetent, and then competent, to stand trial.

He was convicted of three murders, but the conviction was overturned. He eventually was convicted on various charges in five cases in Buffalo and Manhattan.

In 1983, Christopher sent The Buffalo News a rambling letter-essay before agreeing to be interviewed at Rikers Island.

“Joseph Christopher – Drafted by the people, signed into the Army, ordered to kill,” he wrote at the top. A few paragraphs later came the punchline: “So it was a baseball game 17 hits and 13 dead if they are dead.”

In the interview, Christopher was asked to explain that.

“I supposedly attacked 17 people, and 13 of them are dead,” he replied.

Throughout the interview, Christopher provided staccato-like responses, with no hint of boasting or remorse.

Excerpt from Joseph Christopher interview with Gene Warner in 1983

“I was ordered to kill,” he said repeatedly. “Who ordered me to kill? Who set up the conspiracy? I don’t know.”

He was asked to reconcile the “13 dead” with the fewer killings that authorities had linked to him.

“The number is irrelevant. The reason ‘they’ kept saying ‘more, more, more’ was to put more pressure on me, to break me down,” he replied.

Christopher truly didn’t seem to know how many people he had killed.

The cabbies

The killings of two Buffalo cabbies were among the area’s grisliest crimes ever.

On Oct. 8-9, 1980, at the height of community fears about the first four shooting deaths barely two weeks earlier, the bodies of Parlor Edwards, 71, and Ernest Jones, 40, were found in the city’s northern suburbs. Both were beaten to death, and their hearts cut out.

Was Christopher responsible?

To many, it seemed like too much of a coincidence. Plus, Christopher later demonstrated that he wasn’t averse to changing weapons. And his own “13 dead” claim makes more sense if the two cab drivers’ deaths were included.

Yet some pointed to the drastically different kinds of attacks and mutilations, wondering whether authorities wanted to pin all the 1980 assaults on the same person.

Pelonero said it was “highly questionable” whether Christopher killed the taxi drivers.

She cited the lack of physical evidence tying Christopher to those beatings. And she noted he never brought them up until a 1986 interview with a prosecution psychiatrist, when Christopher said other things that couldn’t have been true.

More importantly, she thinks the killer’s “signature” is different in the cabbie deaths.

“The signature is the message the killer wants to leave behind,” she said. “The signature in the shootings and stabbings is identical: blitz attack, hit and run, quick attack and leave.”

That couldn’t have been the case with a prolonged beating followed by a time-consuming surgical task.

In the 1983 Rikers Island jail interview, Christopher was asked about the taxi killings.

“I’m not denying anything,” he replied. “I don’t want sensationalism.”

But minutes later, he vehemently denied an attempted knife attack on another black man on New Year’s Day, 1981.

The book

Pelonero grew up in Holland, in southeastern Erie County, and was in grade school when the killings began. Her late father, Salvatore J. Pelonero, was a Buffalo police officer for 34 years.

When her sister Trieva suggested she write about the 1980 killings, Pelonero barely remembered the case.

But then, learning that court transcripts and other records would be available, she became intrigued about a killing rampage from her hometown.

The more she looked into it, she began to question reports that Christopher was a pathological racist who wanted to start a race war. But she refused to hold any preconceived notions about the man.

“I did not have a horse in this race,” she said. “If I had found Joseph Christopher was a white supremacist or a career criminal, I would have written that. But that’s not what happened. That makes it more tragic.”

Pelonero has interviewed 34 people so far: detectives, prosecutors, defense attorneys and psychiatrists, as well as friends, relatives, neighbors, high school buddies and teachers dating back to third grade.

Her new book, “Absolute Madness: A True Story of a Serial Killer, Race and a City Divided,” is set to be published in the fall of 2017 by Skyhorse Publishing.

Through her research, Pelonero sees three Joseph Christophers.

First, the thoughtful, sweet and kind young man who mowed neighbors’ lawns or shoveled their sidewalks, and was a loyal friend.

Then there was the young man in his early 20s, who learned his mind was unraveling and reached out for help.

And, finally, the tortured Joseph Christopher strangled by his mental disease.

“Joseph Christopher was a man who was pitifully mentally ill who was killing out of terror and mental confusion,” Pelonero said.

But retired Erie County District Attorney Edward C. Cosgrove, who led the original investigation, had another view.

“God bless his soul,” he told The News in 1993, “but he was an unfortunate wretch.”

email: gwarner@buffnews.com

Photos courtesy of The Buffalo News.